Why am I so interested in dreams? One answer is that some time back I had what Carl Jung called a “big” dream. This is one that stays in your memory for days, weeks, even years. We’ve all had them. I like to give my dreams names. I called this big dream “The Museum” because aspects clearly related to a recent visit, with my sister and my young sons, to the Natural History Museum. But the Museum dream mixes up these recent events with more darker ones that happened 30 years earlier when I was just 3 years old.

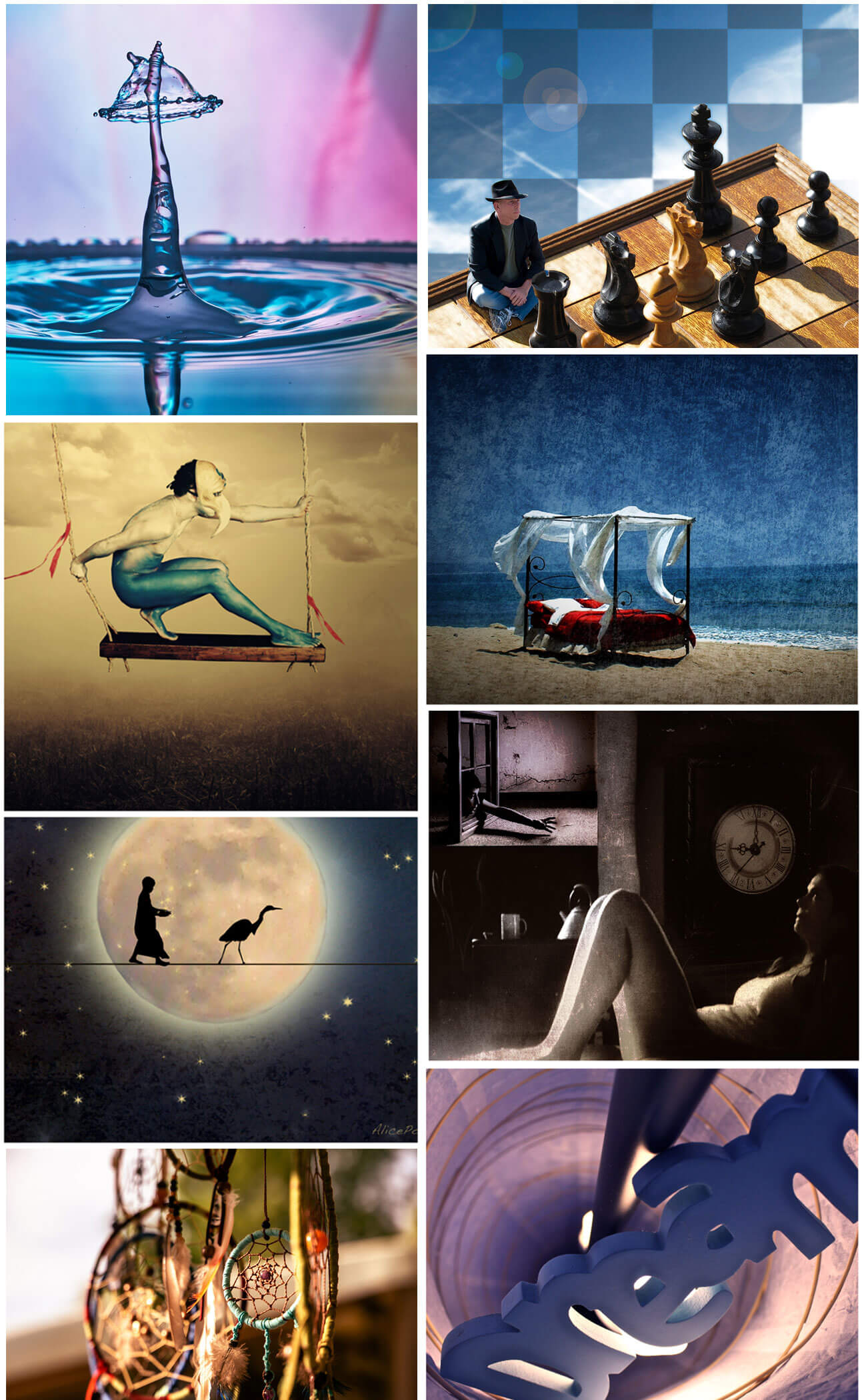

Four scenes from “The Museum” all the dream illustrations on my website are by Becky Ritchie http://@beckyritchieillustration http://www.beckyritchie.co.uk

Scene 1

I’m standing outside the museum. The railings are all around me.

Scene 2

I’m inside the museum. I’m on a search, but I don’t know what I’m looking for.

Scene 3

I’m in a corridor and rising quickly, at the end there’s an opening with a brilliant light.

Scene 4

I’m falling out of the building (or was I pushed out?). I’m terrified. My head will be impaled on the railings. I’m going to die…

This big dream about the museum led to big questions: Why do dreams take fragments from different experiences and put them together? Why do impossible things happen in dreams? Why are dreams timeless? Do dreams have meaning? Do dreams drive our important decisions? Do dreams predict the future? I became hooked on dreams.

My book, “What do dreams do?” is a child of this passion. It tackles these and other questions many of us have. The book draws on my years of experience researching and publishing in leading academic journals but the book is a cross-over, meaning it’s aimed at a general audience who are interested in understanding dreams. I wasn’t an obvious candidate to research dreams. The world of dream research is populated by psychologists, psychiatrists, neuroscientists and philosophers.

I planned a career in psychiatry or psychology but, at university, I did joint Honours in Econometrics and Political Theory instead. In my final year I fell pregnant with my eldest son then took time out to raise three boys! When I returned to work I took a university research post in accounting and finance and did an MSc in Social Research. My PhD was in professional roles and identities. I worked on a social care project before getting my first lectureship in management accounting. I became a Professor eight years after that and remain an active academic. Then “The Museum” happened. For a while I had this gigantic, academic side-line that connected to my earlier plans to be a psychiatrist or psychologist. Now it’s my main- line.

So, I have a non-standard career and am an outsider who can get away with behaving like one. Fortunately, dream researchers are diverse and interdisciplinary group. I feel at home. I’ve synthetized work from beyond the normal research boundaries. I’ve looked to what is known about the lives of early humans, read Freud, along with current neuroscience on memory processes during sleep, located my work within research on brain networks and linked dreams with creativity and psychopathology. Perhaps surprisingly, I argue that we have to go right back to our gatherer-hunter days to understand what dreams do.

What is a dream?

In the end I think dreams portray a pattern in our past experience. For gatherer-hunter humans, this pattern would have been something detectable in the way humans and animals behaved as they moved about to get food and water in their environment. When do predators visit the waterhole? But also when do potential mates or aggressive competitors? There are no certainties when it comes to the behaviour patterns of living beings- they can always surprise us- but there are tendencies, which we can use to avoid predators or meet mates. Lions tend to visit at night, for example. But in the dry season they can get so thirsty they visit in the day. Identifying the behavioural patterns would have involved associating elements of different experiences which happened at different times.

On approach to the waterhole, what is the flash of yellow in the undergrowth? Will it turn out to be a “sit and wait” predator like a lion?

Is the flash of yellow a predator ?

Or is it just a yellow butterfly?

Knowing the pattern of predator visits means we can assess the likelihood that the flash of yellow is a lion. Do we freeze or flee? Whatever we decide, we have to be quick. Also we can’t chance getting close enough to see if that flash of yellow is just a butterfly because if it’s a lion we’d be eaten. For early gatherer-hunter humans most of our decisions would have been instinctive and unconscious. There was no time to think about the pros and cons of what to do. Unconscious knowledge still drives the crucial, split second decisions we take in dangerous situations. But, back then, threats were an everyday occurrence. I maintain the backstory of dreaming is that we dreamed to survive.

But what does all of this mean for us now? Contemporarily, our daily lives are much less precarious and dangerous than back in our gatherer-hunter days. But research shows that dreams still associate elements of different events to identify patterns in our past experience. Also our conscious minds are just the tip of the iceberg – 95% of our brain activity is unconscious.

95% of the iceberg represents unconscious brain activity

Retained dreams may be just a part of this. Many of us think that both dreams and creative insights come from the unconscious. Our dreams make us creative but unconscious patterns in our experiences also compel our big decisions: when we choose a mate, a career or a place to live. To quote Freud: “When making a decision of minor importance, I have always found it advantageous to consider all the pros and cons, in vital matters, however, such as the choice of a mate or a profession, the decision should come from the unconscious, from somewhere within ourselves.” Our big dreams may be for our big decisions.